Exploring the use of Gaussian splatting to simulate real locations.

Visual simulation gaussian splatting

Since our previous article, the interest and activity surrounding gaussian splatting has by no means waned, as can be seen from the large number of scientific articles or the integration work in tools such as Luma-AI or Postshot.

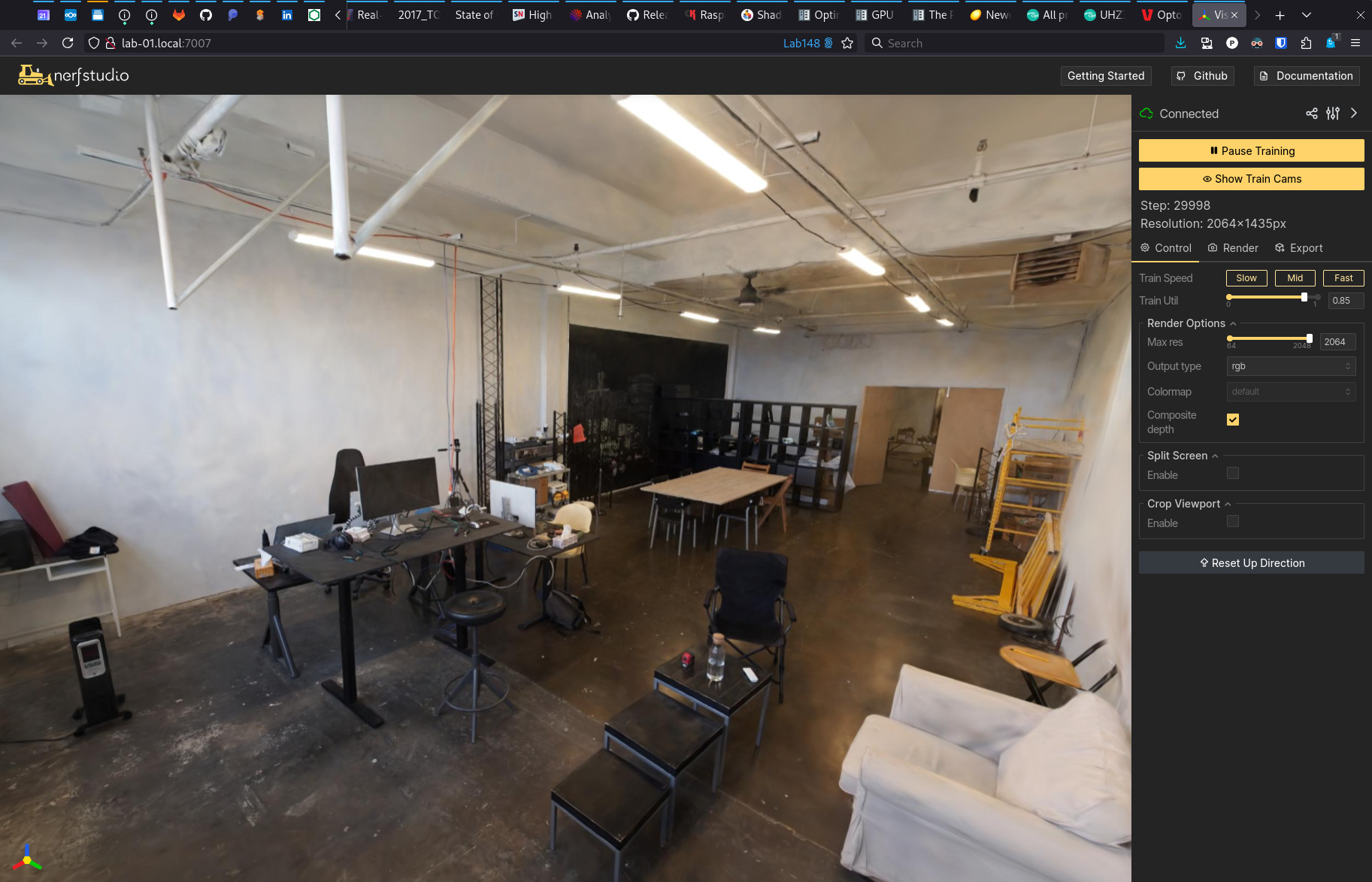

One of the most obvious uses of gaussian splatting for real 3D scene representation is the simulation of physical locations. Whereas “traditional” photogrammetry requires the skills of a 3D graphic artist to achieve a visually convincing result, gaussian splatting is more easily, and more automatically, visually credible. And visible defects are often pleasing to the eye.

We therefore want to check the feasibility of simulating real spaces, using gaussian splatting, in collective immersion situations. That is, in immersive devices such as domes and other immersive rooms of various geometries.

Apart from the visual proximity of the simulation, we have other constraints. The rendering must be displayed at 1:1 scale, so that users feel immersed in the simulation. Rendering must be done in real time, which implies sufficient refresh rate and low latency. It must be possible to augment this simulation with virtual objects. And we want to be able to navigate in the simulated location.

Now that these conditions have been met, let’s see how we can integrate gaussian splatting into a rendering pipeline.

Gaussian splatting in a rendering pipeline

We have explored in particular the use of Gaussian splatting in 3D engines, with an emphasis on open-source tools. We therefore focused on Blender, Godot and, to a lesser extent, Unreal and Touch Designer due to their large user base.

We have compared several addons with the previous tools. Although not a complete comparison, it enabled us to assess the usability of gaussian splatting in our working methods.

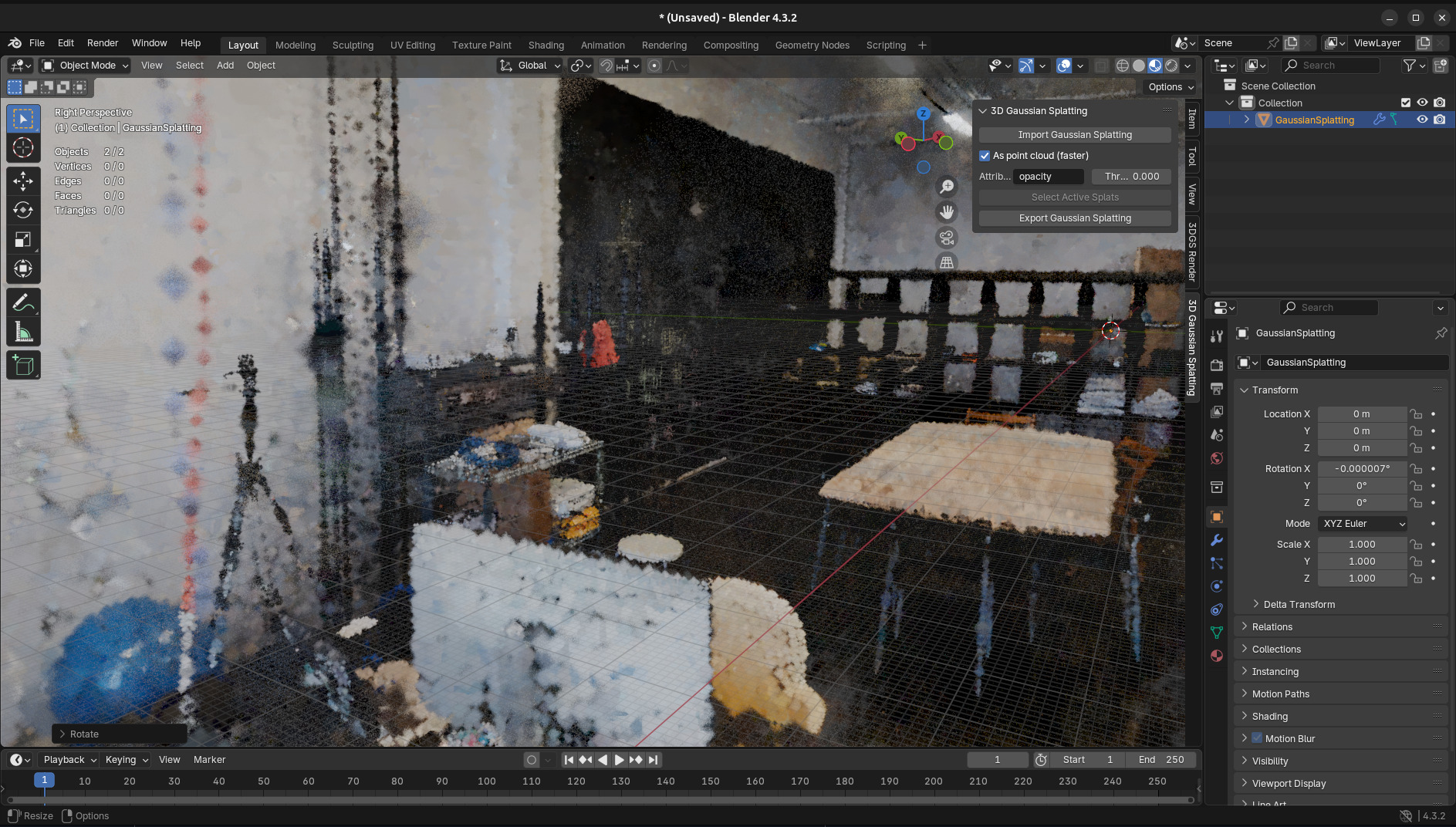

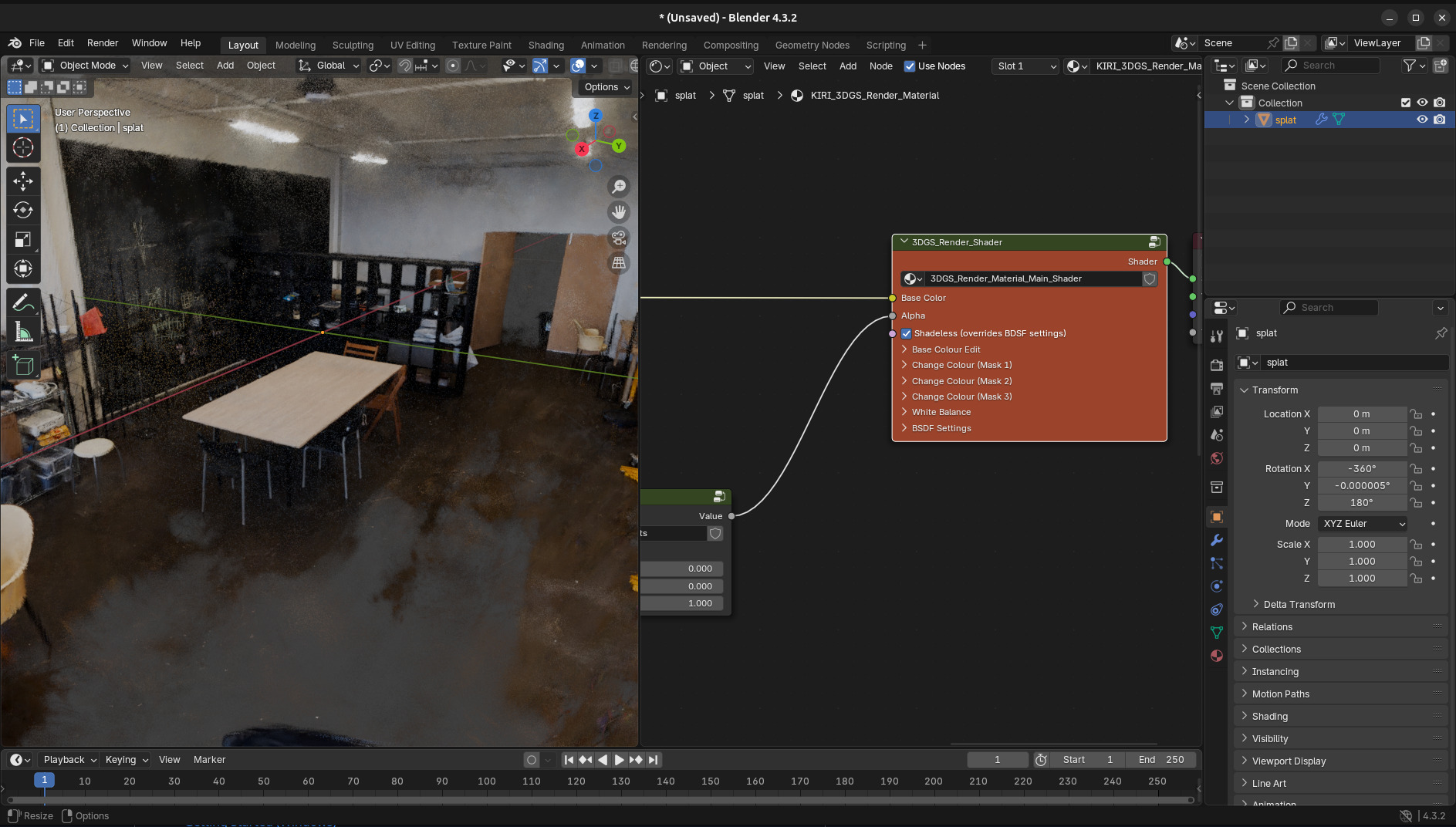

On the Blender side, the most mature implementation is that of KIRI Innovation. It is very complete, and in particular allows you to edit the model and then re-export it. This addon can also render other objects in addition to gaussian splatting, although not in a real-time context. Another very complete addon exists, Splatviz. However, it has the disadvantage of being based on CUDA and therefore only works on NVIDIA graphics cards. Finally, let’s mention the addon proposed by Reshot AI which has the particularity of rendering 3D Gaussians as instances of cubes, making it easy to manipulate, at the expense of visual quality.

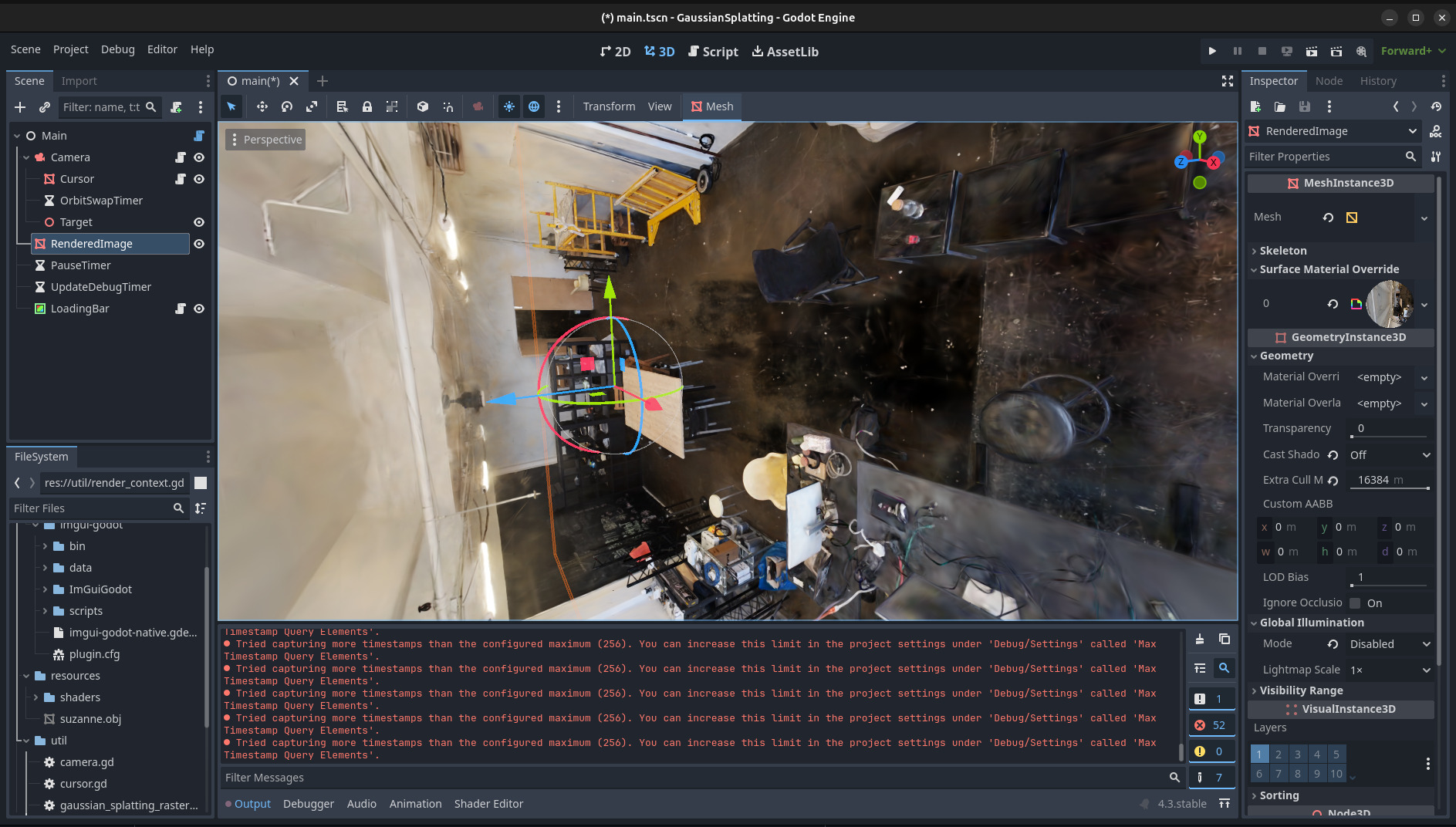

As far as Godot is concerned, the situation is less stellar, as implementations are very preliminary. Two addons are worth mentioning: by Haztro, and 2Retr0, two Github users. Both are proofs of concept, and their integration into Godot is very partial. In particular, it is not (easily) possible to integrate other objects into the scene. For the curious, 2Retr0’s implementation is much smoother than Haztro’s.

For Unreal, developments are more advanced. Several plugins are particularly interesting. First of all, the one proposed by XVERSE Technology. Very complete, it enables you to use gaussian splatting along regular 3D objects, and to make some light touch-ups. However, it only runs under Windows, and the source code is not available. Another option is the plugin from Akiya Research Institute, which has similar features except that it also runs on Linux, and has to be paid for. Finally, Luma-AI offers its own addon, which complements its online offering and phone application.

Finally, the most mature implementation available for Touch Designer seems to be the one proposed by Tim Gerritsen. We haven’t tested it, but it seems usable in a real-time context.

So there are ways of integrating Gaussian splatting into our projects and using it for space simulation purposes. However, there is one important limitation: none of these implementations allow immersive rendering (cubemap, dome master, or equirectangular projection) in real time.Blender obviously isn’t designed for this (although it wouldn’t be the first hijacked use to our credit.And the plugins for Unreal and Touch Designer aren’t suitable either, since rendering is calculated according to camera direction, which only works correctly for rectilinear views.

And, let’s face it, we want to go for open-source approaches, ideally under Linux.

So there’s still a lot of work to be done before gaussian splatting can be used satisfactorily in the context of location simulation in an immersive space.But there is one avenue we’d like to explore: converting gaussian splatting into a 3D mesh, since it seems that using a cloud of Gaussian splats opens up different possibilities to traditional photogrammetry.

Conversion to 3D models

We have therefore tested the most important tools for converting gaussian splatting into 3D meshes, to the best of our knowledge. Most of these tools are also capable of generating gaussian splatting from images.The tools in question are:

- SuGaR,

- NeRFStudio,

- gs2mesh,

- gaustudio,

- 2DGS,

- Luma-AI

- and Meshroom, to provide a basis for comparison with a traditional photogrammetry tool.

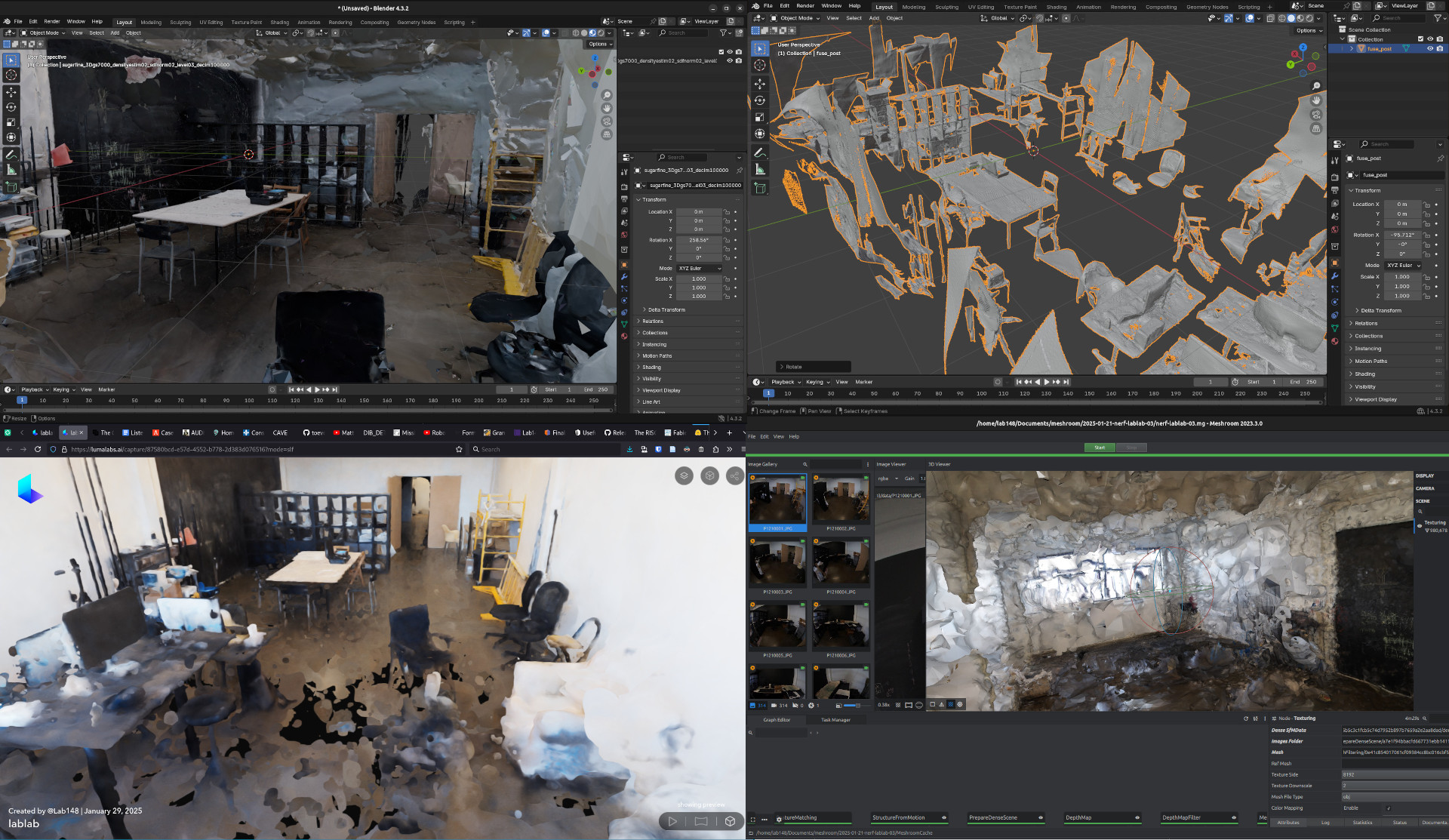

Here’s a typical overview of results obtained with methods based on Gaussian splatting, with SuGaR, 2DGS, Luma-AI and Meshroom in that order:

Three things stand out. Firstly, it’s far from perfect. At best, 3D mesh generation from gaussian splatting falls back on the same problems as traditional photogrammetry, namely that specular or uniform surfaces are excessively poorly represented, as are plain surfaces. Surprisingly, 2DGS generated a fairly clean mesh… but only for a portion of the objects. As it stands, the meshes generated are not usable in a simulation context. Even the 3D model generated by Luma-AI leaves something to be desired: in addition to being very filtered, it has the same limitations. The ground is made of shiny concrete and the hole is clearly visible here.

However, these results are better, in some respects, than those obtained with Meshroom. The representation of individual objects, such as furniture, is superiour. We can therefore anticipate that mesh generation should be quite usable when applied to individual objects, instead of complex scenes.

In any case, this is a dead end, albeit a temporary one. Mesh generation as implemented in these tools is indeed based on methods usually applied to point clouds: Poisson reconstruction, marching cubes, truncated signed distance fields, among others. There is therefore room for the development of methods specifically dedicated to Gaussian splatting, and indeed this is the case if recent literature is to be believed. But it’s still far from being accessible.

Conclusion

With these few tests and experiments, the conclusion is rather clear and ultimately rather expected: gaussian splatting is still in its infancy, its adoption in digital creation tools is in its infancy, and much remains to be done.

However, the situation has greatly evolved since our previous article. There are more, better integrated tools, and the documentation surrounding gaussian splatting is more extensive, as are implementation examples. The visual results are there for all to see, and the technique has great appeal.

So we’ll be keeping a close eye on developments. And for our part, we’re planning to get in on the action by pushing forward the immersive rendering of gaussian splatting. It remains to be seen at what level: our intuition leads us to believe that for the simulation of frozen scenes, integration into our videomapping software would be a good way forward. To be continued!